Persian is one of the world’s oldest Indo-European languages with a tradition stretching back over 2,500 years: from Achaemenid Old Persian to Sassanid Middle Persian (Pahlavi), and on to New Persian from about the 9th century onward (also called Farsi, Dari or Tajiki). That record shows the language has endured across centuries.

Its poetry is rich in many forms: epic verse, lyrical ghazals, Sufi mystic poetry, and live Naqqāli storytelling (a UNESCO‑listed recited tradition of stories like the Shāhnāma). Persian metre (ʿarūz) blends Arabic-derived patterns with local rhythms. Poets often use iconic poetic symbols like garden, wine, nightingale, candlelight and spiritual longing to add myth, emotion, and spirituality into verse.

Poetry isn’t a museum piece in Persian culture; it’s lived. Every Nowruz, people read Hafez aloud under a Haft‑sīn table to share wishes. Ta’ziyeh plays, public music, and calligraphy bring verse alive at festivals. Poetry appears even in ordinary talk or simple visual art.

To keep the spirit and beauty of Persian verse alive on screen, filmmakers often include poetic dialogue, narration, or symbolism in their work. More importantly, directors bring a poetic point of view to their craft. They use like long, quiet shots, natural light, open-ended images, and everyday detail to build mood and meaning, creating scenes that feel like visual poems. This style, known as poetic realism or “open image,” allows viewers to connect emotion and reflection in subtle way.

Persian language and poetic sensibility are not only in dialogue but in how filmmakers frame, pace, and breathe life into each shot. Through this cinematic vision, the essence of Persian poetry continues to shape the soul of Iranian film.

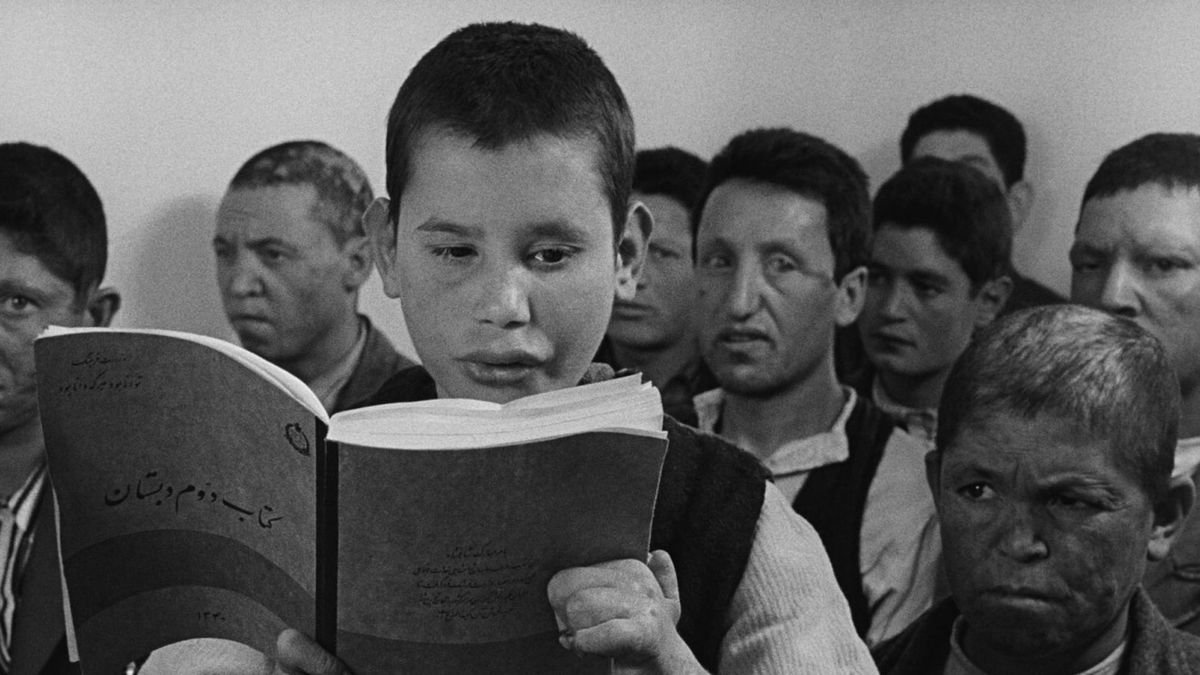

The House is Black (Forugh Farrokhzad)

The House Is Black is the only film directed by the renowned Iranian poet Forugh Farrokhzad. The short black-and-white documentary focuses on a leper colony near Tabriz, following residents as they live, learn, pray, play, and find moments of joy and community while facing isolation from the wider world. Farrokhzad pairs stark images with powerful narration drawn from the Old Testament, the Qur’an, and her own poetry. Farrokhzad’s voice turns every frame into cinematic verse. She finds beauty in faces marked by illness and sees humanity where others turn away. The film doesn’t offer pity; it offers presence. Instead of despair, it gives us quiet strength and compassion. If you want to experience Persian poetry in motion, this is the film to see.

Chess of the Wind (Mohammad Reza Aslani)

Chess of the Wind takes place inside a decaying aristocratic mansion, where a paralysed heiress and her scheming family fall into a web of distrust, betrayal, and murder as they fight over a large inheritance. Secrets build, loyalties change, and hidden desires come to light behind every grand doorway. Director Mohammad Reza Aslani, who was also a poet and critic, shapes the narrative like a decadent poem; every object and space feels full of meaning. While the dialogue seldom echoes classic verses, the film resonates with the aesthetics of Persian classical art. The corridors, cabins, and manor rooms do more than show a setting; they reflect the ambition, decay, and societal transition. If you’re curious about how Persian cinema can feel like visual poetry, this is a perfect place to start.

Close‑Up (Abbas Kiarostami)

Close-Up blends documentary and fiction to tell the true story of a man who pretends to be a famous filmmaker, and convinces a family they’ll star in his next film, until the truth unravels and all are swept into a gripping real-life trial, with everyone reenacting their own roles. What begins as a trial becomes something much deeper, a moving look at identity, dreams, and the need to be seen. Kiarostami films real people, in real spaces, but gives their words and actions a gentle rhythm, and ordinary moments start to feel like poetry. There are no quoted verses, but its structure, composition, and emotional honesty feel close to the spirit of Persian poetry, filled with ambiguity, longing, and reverence for language and image. If you’re curious about how Persian cinema can feel like a poem, this is one of the best places to begin.

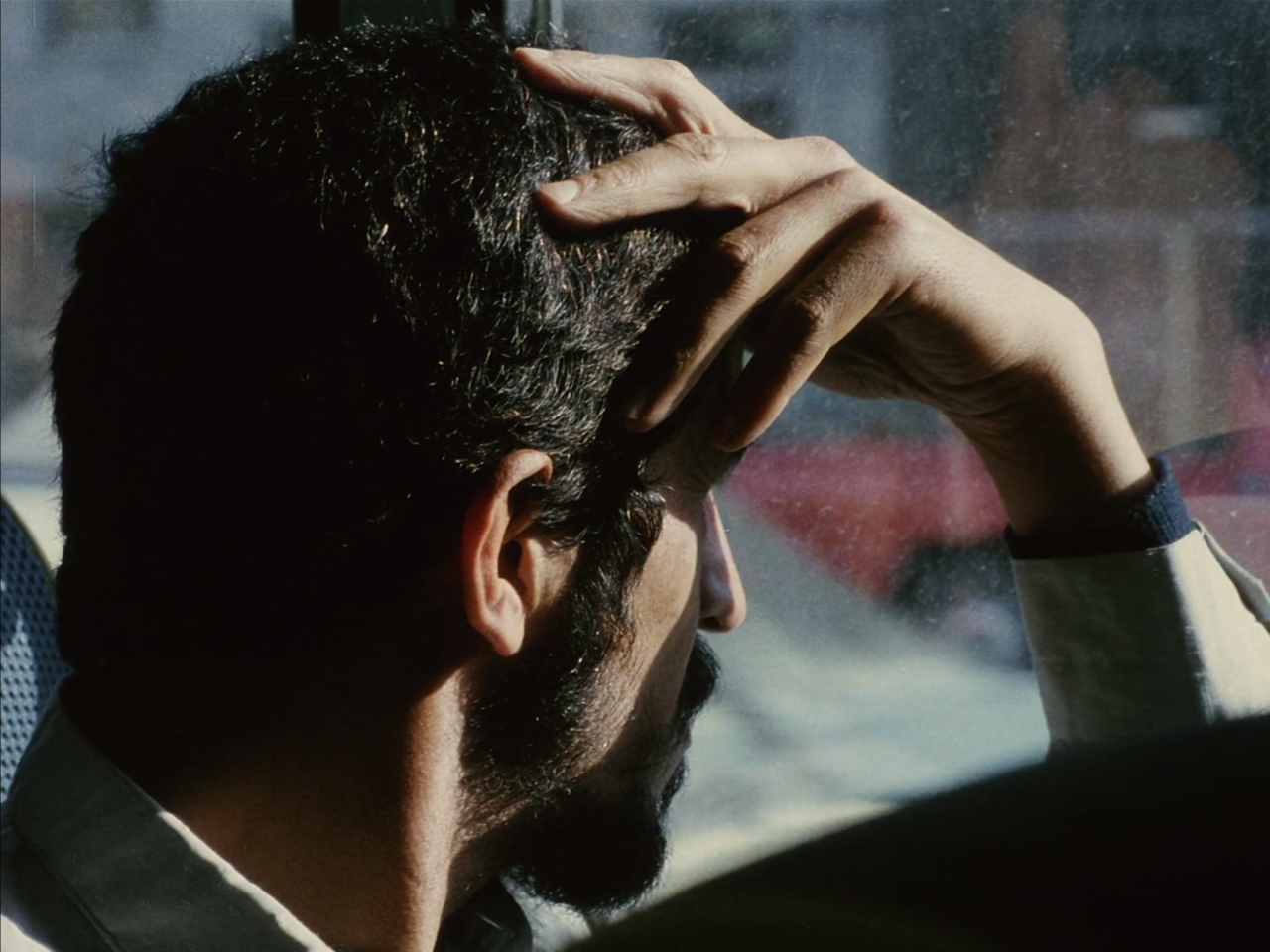

Taste of Cherry (Abbas Kiarostami)

Taste of Cherry is more than just a film. It’s a poetic meditation on life’s deepest questions, told with masterful restraint. The story follows Mr. Badii, a middle-aged man driving through the dusty edges of Tehran. He asks strangers for one thing: to bury him if he chooses to end his life the next day. Each meeting becomes a small conversation about life, death, and what makes living worth it, and the “taste of cherries” symbolises simple joys that might hold him back from despair. Kiarostami’s camera watches the world like a poet; the shots are calm and open. There’s not much talking, and the silence gives you time to think, as if every scene feels like a short poem. This film speaks in the quiet voice of Persian poetry. It is full of honesty, stillness, and space to reflect.

The Wind Will Carry Us (Abbas Kiarostami)

The Wind Will Carry Us follows an “engineer” and his team who arrive in a remote Kurdish village, waiting to film a funeral. But the old woman they’ve come for doesn’t pass away. As days go by, the film becomes a slow, thoughtful look at daily life, death, and slowly gets pulled into the pace of the village. Kiarostami films the village’s slopes, stairways, and distant hills like visual poetry. Scenes repeat, dialogue is quiet, silence carries weight, and small moments feel ripple with meaning. The film uses poetic voice, occasional Khayyam verse, and image-based symbolism to channel the spirit of Persian poetic tradition, making it a great film if you’re interested in simply films that use poetry, landscape, and gentle observation to reveal life’s subtle mysteries.